Gerta Ital : Sudden Enlightenment

Unfortunately, most people who have decided to start working on themselves are usually too impatient. They want to see ‘successes’ as soon as possible, otherwise they feel that Heaven hasn’t taken note of their efforts. It is a strange paradox: nobody objects to the long years of training and study which are necessary for most professions (in the case of academic professions this period of study never really ends), nobody finds it strange that famous actors, writers and artists have to sacrifice their lives to their vocations, but everyone seems to expect instant success on the spiritual path, which is the most difficult and arduous undertaking in the world. It is extremely important to nip such wildly unrealistic expectations in the bud, for they present a very serious obstacle to progress.

A frequent objection raised at this point, even by very well-educated people, is that ‘one often reads that it (enlightenment) happens terribly suddenly, just like that, even in the case of children…’

It is important to point out that what is often described as ‘sudden enlightenment’ in Zen literature is not something which is ever attained suddenly, or even quickly, not even in the case of children who become enlightened. It is always the result of hard, untiring spiritual work, in many many incarnations.

Not even the Buddha of our age, Gautama, was an exception to this rule. Even in his last incarnation he had to devote many lonely years of struggle and unbelievable sacrifice to ascetic exercises and meditation before he could attain the perfect, cosmic enlightenment which finally made him a World Teacher.

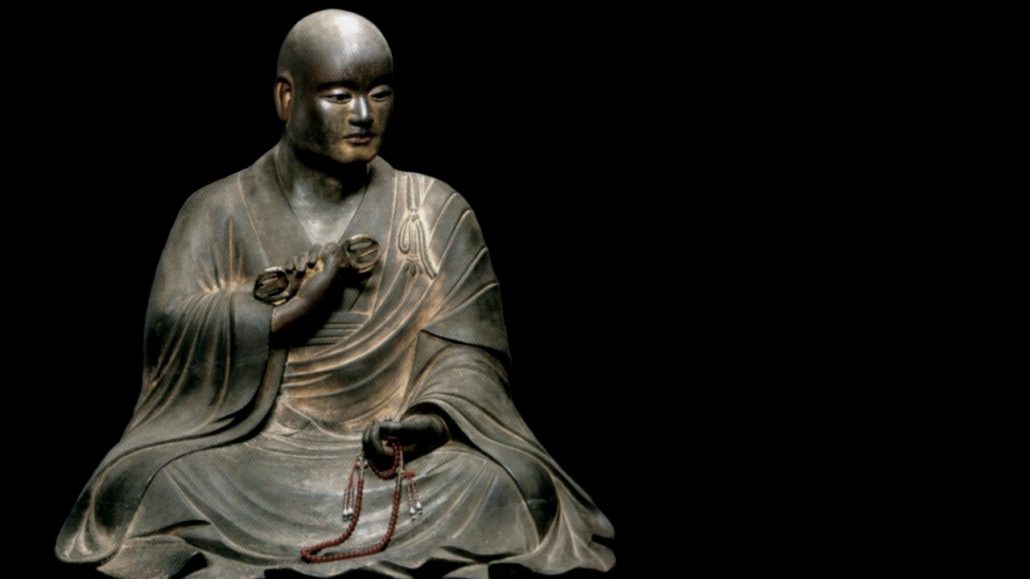

Bodhidharma, who brought Buddhism to China from India in the year a.d. 520, and who lived a life of almost inconceivably strict asceticism himself, made no bones whatsoever about the discipline necessary on the path. When Eka, a very wise and scholarly monk who was later to become his successor came to him for instruction, under exceedingly difficult circumstances, Bodhidharma is reported to have said the following words to him:

The incomparable doctrine of Buddha can only be understood after a long and hard training, through bearing that which is hardest to bear and through the practice of that which is the hardest to practice. People of limited virtue and wisdom whose hearts are shallow and full of self-conceit are not capable of realising the truth of Buddha. All the efforts of such people are certain to be wasted and worthless.

There is no end to the examples one could cite of the extreme hardships which the great Chinese Masters, and the Japanese Masters who were to follow them, voluntarily bore for the sake of their great goal. But even such examples, legion though they may be, are not enough to convince those who stubbornly cling to the occasional reports of ‘sudden enlightenment’, and who are not capable of understanding that such breakthroughs can only be the culmination of endless years of rigorous spiritual discipline. This discipline is an absolute precondition, there is no way around it.

If this were not the case there would be nothing to prevent the fortuitously enlightened individual from leading a dissolute and worldly life, for he would not have the maturity which one needs in order to be able to cope with the ultimate experience.

Even after their enlightenment all the great Masters have lived very simple, strictly ascetic lives. Nor is it enough to dive into the sea of enlightenment once only, and then never again. After the first experience of enlightenment the connection with Eternal Wisdom must be refreshed every day thereafter, in order to ensure that it is never ever broken, not even for a single day. This does not mean that the actual moment of ‘contact’ with the Original Source, something which only takes place after a long period of incredibly strenuous and sincere spiritual exercises, is repeated again and again; it simply means that the seeker’s connection with this eternal and absolute plane of Being must be deepened and made more complete and perfect by daily meditation.

It is only through this ceaseless process of deepening one’s connection with the Absolute that one is able to become, and remain, a vehicle for ‘That’, or ‘It’. The objective is not one’s own happiness and bliss but to create a stage on which ‘That’ can manifest Itself in this world, no matter how small that stage may seem to be in relative terms. Becoming a vehicle for the Absolute means that although one still thinks, one is no longer the thinker, and although one still acts one is no longer the doer. The confidence and detachment from worldly matters which are associated with this state of consciousness are something which can only be fully understood by those who are themselves in the same state.

Laisser un commentaire