A most essential question

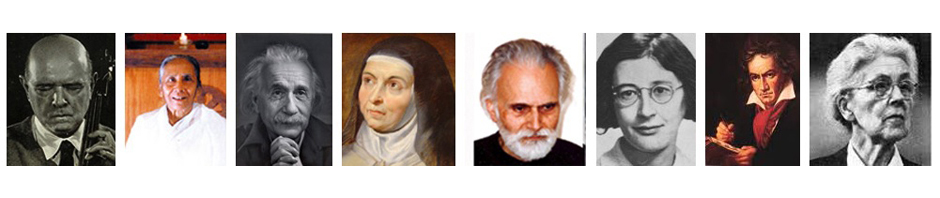

What convergence is there between the journey of the ascetic Tibetan yogi Milarepa and that of the little-known great French mystic of the Seventeenth Century, Madame Guyon ? between Ramana Maharshi and the famous sufi Al-Hallaj ? What is the common denominator between these extraordinary beings who, in such apparently dissimilar ways, climbed the rungs leading to the ultimate realization ? Is it not a question of the greatest importance, to conjecture about what is essential and what is of incidental value, about what is truly the core of a practice and what relates to a cultural context and epoch ?

Jeanne de Salzmann : I am open to a new intelligence

/0 Comments/in Gurdjieff, Right effort, Time and eternal presentJeanne de Salzmann (1889-1990) in her hundredth year in New York

Ian Stevenson’s research about reincarnation

/0 Comments/in Death, Reincarnation rebirth karmaStevenson considered that the concept of reincarnation might supplement those of heredity and environment in helping modern medicine to understand some aspects of human behavior and development. He traveled extensively over a period of 40 years to investigate 3,000 childhood cases that suggested to him the possibility of past lives. Stevenson saw reincarnation as the survival of the personality after death, although he never suggested a physical process by which a personality might survive death.

Stevenson conducted field research into reincarnation and investigated cases in Africa, Alaska, Europe, India and both North and South America, logging around 55,000 miles a year between 1966 and 1971.He reported that the children he studied usually started to speak of their supposed past lives between the ages of two and four, then ceased to do so by seven or eight, with frequent mentions of having died a violent death, and what seemed to be clear memories of the manner of death. After interviewing the children, their families, and others, Stevenson would attempt to identify if there had been a living person who satisfied the various claims and descriptions collected, and who had died prior to the child’s birth.

Stevenson’s research is associated with a ‘minimalist’ model of reincarnation that makes no religious claims. Stevenson believed the strongest cases he had collected in support of this model involved both testimony and physical evidence. In over 40 of these cases Stevenson gathered physical evidence relating to the often rare and unusual birthmarks and birth defects of children which he claimed matched wounds recorded in the medical or post-mortem records for the individual Stevenson identified as the past-life personality.

The children in Stevenson’s studies often behaved in ways he felt suggestive of a link to the previous life. These children would display emotions toward members of the previous family consistent with their claimed past life, e.g., deferring to a husband or bossing around a former younger brother or sister who by that time was actually much older than the child in question. Many of these children also displayed phillias and phobias associated to the manner of their death, with over half who described a violent death being fearful of associated devices. Many of the children also incorporated elements of their claimed previous occupation into their play, while others would act out their claimed death repeatedly.

Stevenson’s fieldwork technique has been said as being that of a detective or investigative reporter, searching for alternative explanations of the material he was offered. One boy in Beirut described being a 25-year-old mechanic who died after being hit by a speeding car on a beach road. Witnesses said the boy gave the name of the driver, as well as the names of his sisters, parents, and cousins, and the location of the crash. The details matched the life of a man who had died years before the child was born, and who was apparently unconnected to the child’s family. In such cases, Stevenson sought alternative explanations—that the child had discovered the information in a normal way, that the witnesses were lying to him or to themselves, or that the case boiled down to coincidence. Shroder writes that, in scores of cases, no alternative explanation seemed to suffice.

Stevenson argued that the 3,000 or so cases he studied supported the possibility of reincarnation, though he was always careful to refer to them as “cases suggestive of reincarnation,” or “cases of the reincarnation type.”

Jean Staune : The history of the Universe

/0 Comments/in Buddhism and the sciences of the UniverseAll the Energy that exists today in the Universe was already present in this tiny point. Since that moment nothing had been « added »

Jean Staune

Take it thus, that I am here in this world and everywhere. I support this entire universe with an infinitesimal portion of Myself. By Me, all this universe has been extended in the ineffable mystery of My being.

Bhagavad Gita (10, 42)

In the same way as water evaporates when heated, and its elements are not lost but transmuted into something finer and more rarefied, so it is with the seeker’s ordinary self after it has passed through the subtle fires of divine alchemy. There is no real loss for it in this crucible, as one may ordinarily suppose, but only transformation into something higher and more refined. Even where outer physical existence is concerned, whatever happens in this domain is nothing but a never-ending process of mysterious transmutation of one kind of life or element into another. Nothing disappears entirely in this Universe and ceases to exist. For where could it go?

The Law of attention Edward Salim Michael

Jean Staune : The history of the Universe

/0 Comments/in Buddhism and the sciences of the UniverseAll the Energy that exists today in the Universe was already present in this tiny point. Since that moment nothing had been « added »

Jean Staune

Take it thus, that I am here in this world and everywhere. I support this entire universe with an infinitesimal portion of Myself. By Me, all this universe has been extended in the ineffable mystery of My being.

Bhagavad Gita (10, 42)

In the same way as water evaporates when heated, and its elements are not lost but transmuted into something finer and more rarefied, so it is with the seeker’s ordinary self after it has passed through the subtle fires of divine alchemy. There is no real loss for it in this crucible, as one may ordinarily suppose, but only transformation into something higher and more refined. Even where outer physical existence is concerned, whatever happens in this domain is nothing but a never-ending process of mysterious transmutation of one kind of life or element into another. Nothing disappears entirely in this Universe and ceases to exist. For where could it go?

The Law of attention Edward Salim Michael

Rabindranath Tagore : I wished that I had the heart to give You my all

/0 Comments/in Hinduism, Right understandingMy hopes rose high, and I thought my evil days were at an end. I stood waiting for alms to be given unasked and for wealth to be scattered on all sides in the dust.

The chariot stopped where I stood. Your glance fell on me, and You came down with a smile. I felt that the luck of my life had come at last. Then all of a sudden You held out Your right hand, saying, “What have you to give me?”

Ah, what a kingly jest was it to open Your palm to a beggar to beg! I was confused and stood undecided, and then from my wallet I slowly took out the least little grain of com and gave it to You.

How great was my surprise when at the day’s end, I emptied my bag on the floor only to find a least little grain of gold among the poor heap! I bitterly wept and wished that I had the heart to give You my all.

Rabindranath Tagore

Remembering of previous lives, the true story of Manika, the girl who lived twice

/0 Comments/in Death, Reincarnation rebirth karmaA true story : a ten years old girl who lived in South of India remembered her previous life when she was in Nepal.

Brother Lawrence : The Practice of the Presence of God

/0 Comments/in Christianity, Compassion and devotionConvince yourself that God is often nearer to us and more effectually present with us, in sickness than in health.

Rely upon no other physician. He reserves your cure to Himself. Put then all your trust in Him, and you will soon find the effects of it in your recovery, which we often retard by putting greater confidence in physic than in God.

Tao Te Ching : Wu-Wei – non action – about duality and Unity

/0 Comments/in Right understandingThen ugly exists.

When everyone sees good,

Then bad exists.

Therefore:

What is and what is not create each other.

Difficult and easy complement each other.

Tall and short shape each other.

High and low rest on each other.

Voice and tone blend with each other.

First and last follow each other.

So, the sage acts by doing nothing,

Teaches without speaking,

Attends all things without making claim on them,

Works for them without making them dependent,

Demands no honor for his deed.

Because he demands no honor,

He will never be dishonored.

from Tao Te Ching – Lao Tze – about Wu-Wei

Meister Eckhart : Temple of God is the Knowing

/0 Comments/in Christianity, Right understanding“ All that God created six thousand years ago and even earlier, when He created the world, He creates all of them right now.”

“ God flows inside creatures, yet He remains untouched by all of them, He has no need of them whatsoever.”

“ His divinity depends on His power to share Himself with whatever is able to receive Him. If He was not sharing Himself, He would not be God.”

“ If you take a fly inside God, this fly is more noble inside God than the highest angel is inside himself. All things inside God are equal, and they are God Himself.”

“ What has no essence, does not exist. There is no creature that has essence, because the essence of all is in the presence of God. If God went out of the creatures even for a single moment, they would disappear into nothingness.”

Bardo Thodol

/0 Comments/in Death, Reincarnation rebirth karma, Tibetan BuddhismThine own consciousness, not formed into antyhing, in reality void, and the intellect, shining, and blissful — these two — are inseparable. The union of them is the Dharma-Kaya state of Perfect Enligtenment.

Thine own consciouness, shining, void, and inseparable from the Great Body of Radiance, has no birth, nor death, and is he Immutable Light — Buddha Amitabha.

Recognizing the voidnes of thine own intellect to be Buddhahood, and looking upon it as being thine own consciousness, is to keep thyself in the state of the divine mind of the Buddha.

To those who have meditated much, the real Truth dawned as soon as the body and consciousness-principle part. The acquiring of experience while living is important : they who have (then) recognized (the true nature of their own being), and thus have had some experience, obtain great power during the Bardo of the Moment of Death, when the Clear Light dawneth.

Bardo Thödol p 95-96 translation W.Y. Evans-Wentz and lama Kazi Dawa Samdup, Oxford University Press.