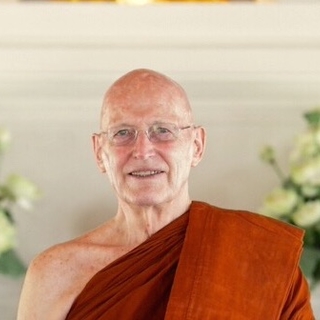

Ajahn Sumedho : The Sound of Silence – Nada –

In the silence of those nights he began to perceive the ever-present inner sound, seemingly beginningless and endless, and he soon found that he was able to discern it throughout the day and in many circumstances, whether quiet or busy. He also realized that he had indeed noticed it once before in his life, when he had been on shore leave from the U.S. Navy in the late ’50s and, during a walk in the hills, his mind had opened into a state of extreme clarity. He remembered that as a wonderfully pure and peaceful state, and he recalled that the sound had been very loud then.

So those positive associations encouraged him to experiment and see if it might be a useful meditation object. It also seemed to be an ideal symbol, in the conditioned world of the senses, of those qualities ol mind that transcend the sense realm: not subject to personal will, ever present but only noticed if attended to: apparently beginningless and endless, formless to some degree, and spatially unlocated.

When he first taught this method to the Sangha at Chithurst that winter, he referred to it as “the sound of silence” and the name stuck. Later, as he began to teach the method on retreats for the lay community, he began to hear about its use from people experienced in Hindu and Sikh meditation practices. In these traditions, he found out, this concentration on the inner sound was known as nada yoga, or “the yoga of inner light and sound.” It also turned out that books had been written on the subject, commentaries in English as well as ancient scriptural treatises, notably the Way of Inner Vigilance by Salim Michael (published by Signet).

In 1991, when Ajahn Sumedho taught the sound of silence as a method on a retreat at a Chinese monastery in the United States, one of the participants was moved to comment, “I think you have stumbled on the Shunrangamaa samadhi. There is a meditation on hearing that is described in that sutra. and the practice you have been teaching us seems to match it perfectly.”

Seeing that it was a practice that was very accessible to many people, and as his own explorations of it deepened over the years, Ajahn Sumedho has continued to develop it as a central method of meditation, ranking alongside such classical forms of practice as, “mindfulness of breathing” and “investigation of the body.” The Buddha’s encouragement for his students was to use skillful means that are effective in freeing the heart. Since this form of meditation seems to be very supportive for that, despite not being included in lists of meditation practices in the Pali Canon or anthologies such as the Visuddhimagga, it seems wholly appropriate to give it its due. For surely it is the freedom of the heart that is the purpose of all the practices—and that freedom is the final arbiter of what is useful and therefore good.

Laisser un commentaire