A most essential question

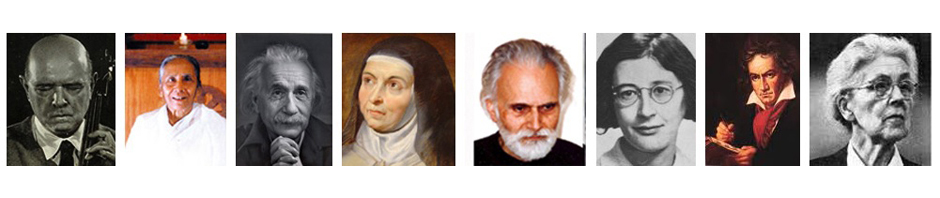

What convergence is there between the journey of the ascetic Tibetan yogi Milarepa and that of the little-known great French mystic of the Seventeenth Century, Madame Guyon ? between Ramana Maharshi and the famous sufi Al-Hallaj ? What is the common denominator between these extraordinary beings who, in such apparently dissimilar ways, climbed the rungs leading to the ultimate realization ? Is it not a question of the greatest importance, to conjecture about what is essential and what is of incidental value, about what is truly the core of a practice and what relates to a cultural context and epoch ?

Maurice Nicoll : what we call the present moment is not now

/0 Comments/in Right understanding, Time and eternal presentNo reveries, no conversations, no tracing out of the meaning of phantasies, contain this now, which belongs to a higher order of consciousness. The time-man in us does not know now. He is always preparing something in the future, or busy with what happened in the past. He is always wondering what to do, what to say, what to wear, what to eat, etc. He anticipates; and we, following him, come to the expected moment, and lo, he is already elsewhere, planning further ahead. This is becoming— where nothing ever is.

We must come to our senses to begin to feel now. We can only feel now by checking this time-man, who thinks of existence in his own way. Now enters us with a sense of something greater than passing-time. Now contains all time, all the life, and the aeon of the life. Now is the sense of higher space. It is not the decisions of the man in time that count here, for they do not spring from now. All decisions that belong to the life in time, to success, to business, comfort, are about ‘tomorrow’. All decisions about the right thing to do, about how to act, are about tomorrow. It is only -what is done in now that counts, and this is a decision always about oneself and with oneself, even although its effect may touch other people’s lives ‘tomorrow’. Now is spiritual. It is a state of the spirit, when it is above the stream of time-associations.

Spiritual values have nothing to do with time. They are not in time, and their growth is not a matter of time. To retain the impress of their truth we must fight with time, with every notion that they belong to time, and that the passage of days will increase them. For then it will be easy for us to think it is too late, to make the favourite excuse of passing-time.

The feeling of now is the feeling of certainty. In now passing-time halts. And in this halting of time one’s understanding has power over one. One knows, sees, feels in oneself, apart from all outer things; and above all, one is. This is the state of faith, as I believe was originally meant—the certain knowledge of something above passing-time. Faith is now.

What the time-man understands about faith is something quite different. Faith has to do with that which is alone in oneself and unknown to anyone else. ‘Every visible state, every temporal, every pragmatic approach to faith, is, in the end, the negation of faith’ (Karl Barth). All insight, all revelation, all illumination, all love, all that is “genuine, all that is real, lies in now—and in the attempt to create how we approach the inner precincts, the holiest part of life. For in time all things are seeking completion, but in now all things are complete.

So we must understand that what we call the present moment is not now, for the present moment is on the horizontal line of time, and now is vertical to this and incommensurable with it.

Ajahn Mun : My determination to transcend Samsara

/0 Comments/in Right effort, Theravada Buddhism“I myself never expected to survive and become a teacher, for my determination to transcend samsara was much stronger than my concern for staying alive. All my efforts in all circumstances were directed toward a goal beyond life. I never allowed regrets about losing my life to distract me from my purpose. The desire to maintain my course on the path to liberation kept me under constant pressure and directed my every move. I resolved that if my body could not withstand the pressure, I would just have to die. I had already died so many countless times in the past that I was fed up with dying anyway. But were I to live, I desired only to realize the same Dhamma that the Buddha had attained. I had no wish to achieve anything else, for I had had enough of every other type of accomplishment. At that time, my overriding desire was to avoid rebirth and being trapped once more in the cycle of birth and death.

“The effort that I put forth to attain Dhamma can be compared to a turbine, rotating non-stop, or to a ‘Wheel of Dhamma’ whirling ceaselessly day and night as it cuts its way through every last vestige of the kilesas. Only at sleep did I allow myself a temporary respite from this rigorous practice. As soon as I woke up, I was back at work, using mindfulness, wisdom, faith, and diligence to root out and destroy those persistent kilesas that still remained. I persevered in that pitched battle with the kilesas until mindfulness, wisdom, faith and diligence had utterly destroyed them all. Only then could I finally relax. From that moment on, I knew for certain that the kilesas had been vanquished – categorically, never to return and cause trouble again. But the body, not having disintegrated along with the kilesas, remained alive.

“This is something you should all think about carefully. Do you want to advance fearlessly in the face of death, and strive diligently to leave behind the misery that’s been such a painful burden on your hearts for so long? Or do you want to persist in your regrets about having to die, and so be reborn into this miserable condition again? Hurry up and think about it! Don’t allow yourselves to become trapped by dukkha, wasting this opportunity – you’ll regret it for a long time to come.

“The battlefield for conquering the kilesas exists within each individual who practices with wisdom, faith, and perseverance as weapons for fighting his way to freedom. It is very counterproductive to believe that you have plenty of time left since you’re still young and in good health. Practicing monks should decisively reject such thinking. It is the heart alone that engenders all misjudgment and all wisdom, so you should not focus your attention outside of yourself. Since they are constantly active, pay close attention to your actions, speech, and thoughts to determine the kind of results they produce. Are they producing Dhamma, which is an antidote to the poisons of apathy and self-indulgence; or are they producing a tonic that nourishes the delusions that cause dukkha, giving them strength to extend the cycle of existence indefinitely? Whatever they are, the results of your actions, speech, and thoughts should be thoroughly examined in every detail; or else, you’ll encounter nothing but failure and never rise above the pain and misery that haunt this world.”

Ajahn Mun was Ajahn Chah’s teacher

Edward Salim Michael – Sadhana and Enlightenment

/0 Comments/in Right effortLike an iceberg whose biggest and most important part remains submerged and hidden from sight, the human being’s most essential aspect lies mysteriously veiled beneath the mists of his illusory ordinary self. And, because the desires and clamors of this perceptible little self are so noisy, he is impelled to notice only this small part of himself, totally unaware of the majesty of his Supreme Nature concealed behind all this wild uproar in him. To arrive at perceiving the huge and vital part of an iceberg covered from view, it is necessary to make the effort of plunging into the waters that surround the small exposed fragment.

Enlightenment reveals how little and insignificant is the visible aspect of the human being, but attaining enlightenment is not easy. Not only does it demand much patient struggle from the seeker but also, and above all, a profound and sustained sincerity.

Edward Salim Michael, The Law of attention

Prajnaparamita

/0 Comments/in Mahayana Buddhism, Right understandingSubhuti asked: “Is perfect wisdom beyond thinking? Is it unimaginable and totally unique but nevertheless reaching the unreachable and attaining the unattainable?”

The Buddha replied: “Yes, Subhuti, it is exactly so. And why is perfect wisdom beyond thinking? It is because all its points of reference cannot be thought about but can be apprehended. One is the disappearance of the self-conscious person into pure presence. Another is the simple awakening to reality. Another is the knowing of the essenceless essence of all things in the world. And another is luminous knowledge that knows without a knower. None of these points can sustain ordinary thought because they are not objects or subjects. They can’t be imagined or touched or approached in any way by any ordinary mode of conciousness, therefore, they are beyond thinking.

Prajnaparamita

One Silent communion

/0 Comments/in The role of Great Art.Whatever their creed or race, and no matter where they happen to be, when a group of people are assembled together, listening to the sublime harmonies and wonderful orchestral “colors” of a great symphonic work secretly imparting to them an ineffable truth through expressions of elevated sentiments, the minds, thoughts, and feelings of all are then united in one silent communion. At that exalted hour, words have lost all their meaning.

Edward Salim Michael The Law of Attention chap 41

Baghavad-Gita : What is knowledge, what is ignorance

/0 Comments/in HinduismA total absence of worldly pride and arrogance, harmlessness, a candid soul, a tolerant, long-suffering and benignant heart, purity of mind and body, tranquil firmness and steadfastness, self-control and a masterful government of the lower nature and the heart’s worship given to the Teacher.

A firm removal of the natural being’s attraction to the objects of the senses, a radical freedom from egoism. absence of clinging to the attachment and absorption of family and home, a keen perception of the defective nature of the ordinary life of physical man with its aimless and painful subjection to birth and death and disease and age, a constant equalness to all pleasant or unpleasant happenings.

A meditative mind turned towards solitude and away from the vain noise of crowds and the assemblies of men, a philosophic perception of the true sense and large principles of existence, a tranquil continuity of inner spiritual knowledge and light, the Yoga of an unswerving devotion, love of God, the heart’s deep and constant adoration of the universal and eternal Presence; that is declared to be the knowledge; all against it is ignorance.

Baghavad-Gita chap 13 – 8-13

The essential condition for the attainment of this supreme goal is the complete absence of the ego-sense. Self-control and self-discipline are the means. Yoga also signifies union with and absorption in the immortal Reality. A steady, persevering, and concentrated effort and struggle alone can lead the aspirant to the realization of the Godhead. So long as man is hankering after the pleasures of the senses, his progress on the path is slow and erratic. He must be undaunted in his endeavor and determined in his purpose. He must leave no stone unturned to subdue and eventually eradicate the impure passions of his heart and mind. A purified and enlightened bud-dhi can alone entitle the sadhaha to enter the kingdom of eternity.

Yoga is not a thing to be merely talked about, read in books, and heard through others. Yoga is for practice in life.

Swami Ramdas – Presence of Ram

Thich Nhat Hanh – Mindful movements –

/0 Comments/in Mahayana Buddhism, The power of attention and meditationMajjhima Nikaya & Visuddhi Maga : The Sublime Reality

/0 Comments/in Right understandingThe Reality that came to me is profound and hard to see or understand because it is beyond the sphere of thinking. It is sublime and unequaled but subtle and only to be found by the dedicated. Majjhima Nikaya

Just as space reaches everywhere, without discrimination, just so the immaculate element, which in its essential nature is mind, is present in all. Visuddhi Magga

The truth is noble and sweet; the truth can free you from all ills. There is no savior in the world like the Truth.

Have confidence in the Truth, even though you may not be able to understand it, even though its sweetness has a bitter edge, even though at first you may shrink from it. Trust in the Truth.

The Truth is best as it is. No one can alter it, neither can anyone improve it. Have faith in the Truth and live it.

The self is in a fever; the self is forever changing, like a dream. But the Truth is whole, sublime and everlasting. Nothing is immortal except the Truth, for Truth alone exists forever. Majjhima Nikaya

Edward Salim Michael : The development of integrity

/0 Comments/in Right effortThe development of integrity and of true being, therefore, is indispensable for the seeker in his spiritual quest.

If he gives a promise he must keep it—no matter how hard it may be for him. He must constantly be wary of any unconscious lying, dishonesty, or inaccuracy, either to himself or to others. He should watch over his thoughts, his speech, and his way of being with people.

He must try to be as honorable and as sincere as he can, both with himself and with all those with whom he has dealings. He has to learn to have compassion for everyone with whom he comes into contact, because he never knows what profound hidden pain and worry this person may be carrying in him. He must become aware of the fact that, in one way or another, all beings suffer.

If, right from the start, moral values do not develop along with his inner spiritual work, then the seeker can be absolutely sure that his struggles will not bring him the true spiritual comprehension and unfolding he is seeking. His misdirected efforts may even accentuate and crystallize his undesirable tendencies, making them yet more difficult to eradicate later.

Fidelity to oneself also means fidelity to others; what one would wish for oneself, one must wish for others too. If a person does not want to be robbed of his happiness, he must not rob others of theirs either. The seeker must begin this spiritual work with the clear understanding that there is nothing in the universe that is not part of the whole. And if each thing is part of the whole, then there is only the One. All beings and everything in the world, as well as all the planets and stars, are parts of the Divine Universal Being in the same way as one’s head, neck, arms, trunk, legs, internal organs, and blood cells are part of the whole of oneself. Whatever harm is done to the one, the whole will inevitably suffer, sooner or later.

That is why there is so much insistence throughout a greater part of the text that follows on moral values and sincerity of being.

The Law of attention (chp Introduction)

The enigmatic problem of self-forgetfulness.

/0 Comments/in Right understandingWhat is of primary importance for an aspirant on this path is to learn to get away from his habitual state of being, the ordinary state into which he constantly falls each time after he has made the vital effort to rise and be connected anew to his Inner Source.

This habitual condition of being—or rather of not being and of not sensing himself—in which the human being generally passes his entire life is the very dragon in him to be overcome and transformed.

If a seeker can really see and understand what takes place in him every time the mists of this strange inner death descend upon him and mysteriously swallow up the awareness he has of his existence, he will have gained a further precious insight into himself and found a weapon with which to combat the enigmatic problem of his self-forgetfulness .

This difficulty can thus be used by a wise aspirant as an additional means to rise spiritually. Each time he catches himself flattering or disliking someone, saying something unkind, being untruthful, or even playing a certain role with people, if he follows up the source whence all these have sprung, he will generally find it to be a form of wrong self-consideration.

This will, in turn, be an alarm signal for him to realize the immediate need there is to try to disengage himself from the grip of his inferior state of being and of feeling himself into which he has once more sunk. The aspirant will find that, each time he makes a genuine effort to redirect his gaze inwardly to dwell in the silence of his true abode, he will at that moment begin to experience a state of pure and uninvolved impersonal awareness.

In this state, there will be neither the time nor the place in him for personal consideration or anything else arising from his lower nature.

Edward Salim Michael The Law of Attention chap 5